Last week a driver deliberately ploughed his car into a crowd of football fans in Liverpool. Footage of the attack shows people bouncing helplessly off the speeding vehicle and others going under the wheels. Miraculously nobody was killed, but dozens were injured, including several children.

In Europe, where guns are rare, cars and trucks are the deadliest weapons in circulation. Terrorists and misfits have used them to kill civilians on many occasions over the past two decades – sometimes in isolation, sometimes as a prelude to a knife rampage. Al-Qaeda and Islamic State have even published tactical guides on how to kill people with a car.

But last week’s attack does not appear to have been political. The police very quickly announced that the perpetrator was a middle-aged white man, with the subtext that he probably wasn’t an Islamist. As further video and eyewitness testimony trickled in, a disturbing picture emerged: The car itself appears to have created the circumstances that provoked the attack. It was motive, opportunity and method.

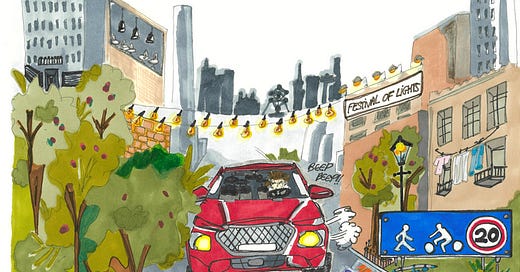

What appears to have happened is as follows. The city was thronged for a huge football victory parade, but a man felt entitled to use his car anyway. When the crowd parted to allow an ambulance to pass, he forced his way in – but then got stuck. Frustrated, he began revving his engine and honking his horn, prompting the revellers to shout and slap his car. The man, allegedly under the influence of drugs, lost his temper and rammed the crowd.

This was an extreme incident but it fits a common pattern. A person in a car feels entitled to priority access to public space. If somebody slows them down they quickly become enraged, blasting the horn and sometimes using the heft of their vehicle to physically intimidate the other person – particularly if they are on foot or on a bicycle. If you spend even a few hours moving about a European city, you’ll see this sequence play out many times.

Citizens wouldn’t normally tolerate such antisocial behaviour. But when the perpetrator is in a car, we do. Despite only about half of urban households owning a car,[1] we have been conditioned to accept their dominance of public space as the natural order of things. This is what urbanists call ‘car brain’.

Undue deference

One of my earliest childhood memories is of being told to “be careful” as soon as I was outside the house. Learning to cross the road safely is now a stage of childhood development. Beyond the direct risk to life, we have sacrificed childhood autonomy and the ability to play carefree in the street.

We now have the technological means to put hard limits on car speeds in urban environments. We actually do so for other vehicles such as electric scooters, citing safety concerns as the reason; but for cars, which are an order of magnitude more dangerous, it’s politically unthinkable.

Besides speeding through urban areas spewing toxic fumes, car owners feel entitled to store their vehicle on land they don’t own for a token fee. For a few tens of euros a year, residents of any city in Europe are allowed store their car on a plot of land outside their house that, at market rates, might be worth €1,000 or more per year.[2] Car storage is the only permitted use for this generous land grant.

Even non-drivers exhibit car brain in the undue deference they show to people behind the wheel. On zebra crossings, those rare parts of a street where cars don’t have priority, it’s common to see pedestrians meekly waving their thanks at drivers who stop for them. Being a car driver means routinely being thanked by members of the public simply for obeying the law.

Tolerated violence

At some point, such outsized feelings of entitlement can lead to violence. As a pedestrian and cyclist who does dare to take up my share of public space, whether by forcing a driver to stop by stepping onto a crossing or by cycling at a safe distance from parked cars, I receive threats of violence perhaps once or twice a month.

I’m generally able to laugh them off, partly because I’m used to it and partly because I’ve spent enough time on the training mats to win a scrap if I need to. But I’m always careful not to get directly in front of an angry driver’s vehicle: As with a gun, a man with a car can kill you in a split second of rage, and no amount of training can protect you from that.

Cars also kill an astonishing number of people by accident – more than 20,000 a year in the EU. Speaking for myself, as a healthy young man without suicidal tendencies, the thing most likely to kill me in the next decade or two is, by some distance, a car.

As I have worked over the years to peel back the layers of car brain,[3] this is what I find most shocking. It’s not that we tolerate the noise, the pollution, the blocked buses and trams, the wasted public space. It’s the fact that millions of people are moving about in a loaded weapon without even thinking about it.

European countries are not known for their lax approach to public safety. We’re governed by all manner of rules to stop us hurting ourselves or each other. Supermarket staff are forced to throw away perfectly good food at the end of each day to avoid a minuscule risk of poisoning a customer. Once they’ve done that, they get home by piloting two tons of metal through a street full of children while scrolling on their smartphone.

This is all a product of ideology. There is nothing inevitable about car dependency, especially in a city; it’s perfectly possible to live without one, and millions of us do. There are now more bicycles than cars in London – and yet the road infrastructure is still oppressively car-focused. The privileges given to cars harm all city-dwellers, while the number who use them dwindles by the year.

Policies to reduce motonormativity would allow even more people to go car-free: The archetypal car-dependent person is the parent too scared to do the school run by bicycle because of all the cars, and who therefore uses a car and becomes part of that very problem.

When something is seen as inevitable, people stop questioning the harms it causes and learn to tolerate things that would, in any other context, be scandalous. If we can break free of our collective car brain, future generations will be shocked that people were allowed to drive such things unimpeded through our precious urban landscapes.

[1] This is an extremely rough estimate based on Brussels, which I imagine to be fairly typical. In any case, car ownership is by no means ubiquitous, as it is in most American cities.

[2] I have written about this at length, and done some rudimentary maths, here.

[3] I’m a recovering petrolhead. I was obsessed with cars as a child, and for the first decade of my adult life I exhibited many of the bad behaviours I describe in this article. A part of me still loves cars; they just don’t belong in the city.

For once, I find myself nodding violently in agreement, Sam ;-) Seriously, especially this bit:

"Being a car driver means routinely being thanked by members of the public simply for obeying the law."

As I, too, peel back the layers of car brain, I have mostly stopped giving that little wave.